SCALES (SAYIDAT AL BAHR)

Friday, December 13, 2019 at 8:19PM

Friday, December 13, 2019 at 8:19PM Stars: Basima Hajjar, Ashraf Barhoum, Yagoub Al Farhan, Fatima Al Taei, Haifa Al-Agha and Rida Ismail.

Director/writer: Shahad Ameen

AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE: November 21, 2020 at the Sydney Science Fiction Film Festival.

WINNER: Best Film, 30th Singapore International Film Festival’s Silver Screen Awards; November 30, 2019.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ½

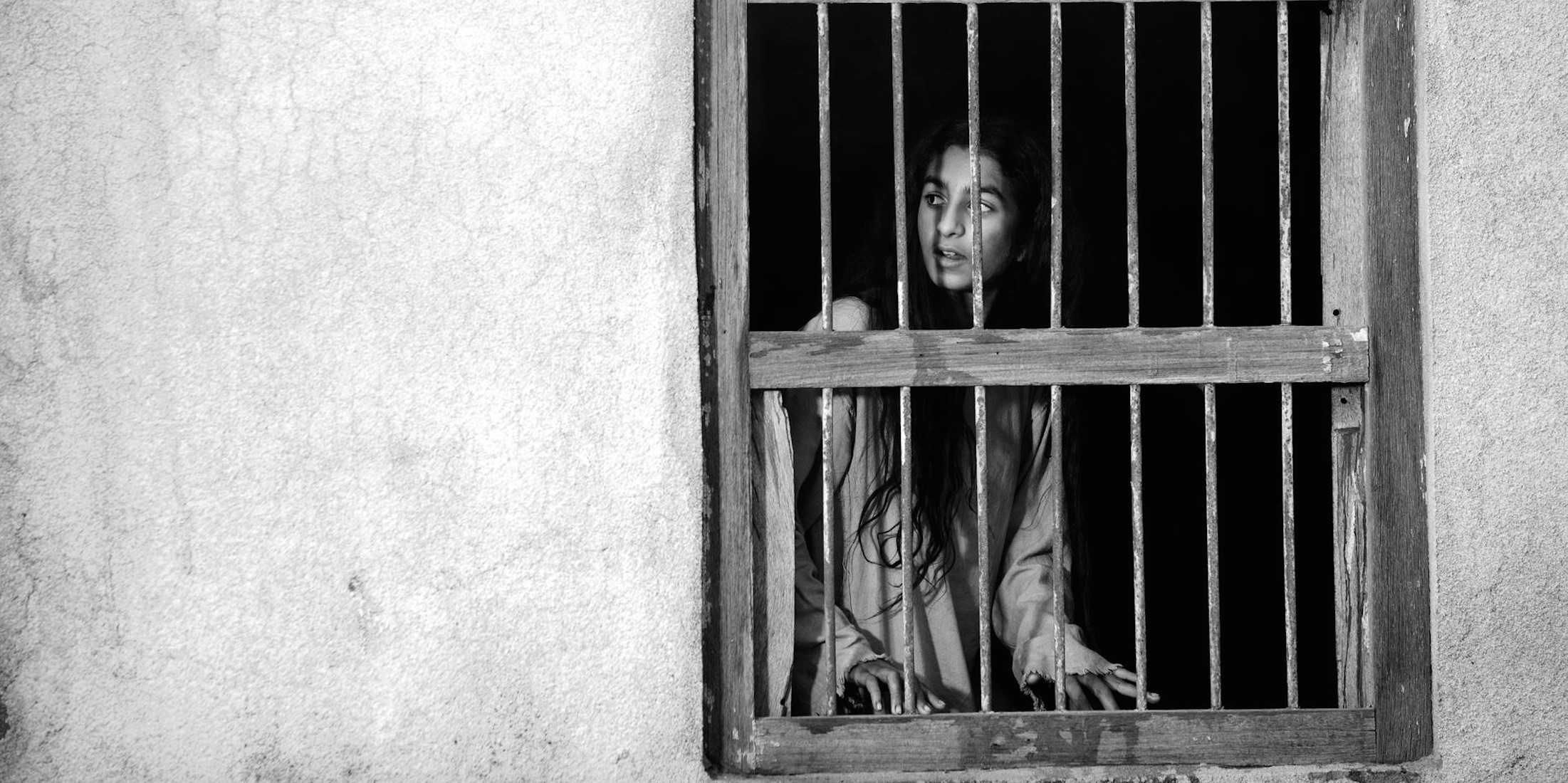

Recalling Niki Caro’s Whale Rider in its melding of tribal mythologies and patriarchal defiance, Shahad Ameen’s Scales is an altogether darker fantasy work marked distinctive by its potent social relevance and chilling imagination. Set against a monochromatic dystopian landscape on the rocky foreshores of a dead sea, where the ‘sea maidens’ of lore survive on the villagers’ offerings of young girls, the Saudi director’s debut feature (a reimagining of the concept she introduced in her 2013 short, Eye & Mermaid) is fairy-tale horror of the highest order.

The sacrifice of young women (disturbingly portrayed in the film’s opening frames) is believed by the village elders to ensure bountiful fishing and enduring prosperity. When young father Muthana (Yagoub Al Farhan) defies the tradition, saving his baby daughter Hayat from the creature’s webbed claw, it is believed he brings ill fortune to his people and a lifetime of derisive shame to his child. Twelve years later, Hayat (the remarkable Basima Hajjar, 15 at the time of shooting) spends her days fending of bullies, staying clear of bitter elder Amer (Ashraf Barhoum) and trying to find a niche for herself somewhere between the responsibilities of the boys her age and the dark destiny facing the girls.

When her bitter mother Aisha (Fatima Al Taei) gives birth to a boy, her fate seems sealed; at the next full moon, she will be led to the water’s edge and given to the sea maidens. However, she survives and is re-evaluated by the men folk when she drags a creature from the deep to her village square.

There is sly humour at work surrounding the relationship between the mermaids and the men in Ameen’s otherwise steely, serious narrative. The elders fear the wrath of the women of the deep but govern ruthlessly women of their own kind. The dichotomy of this suggests their beliefs, based on age-old traditions, are confused and kind of ridiculous. In a broader context, the villager’s relationship with the ocean creatures represents how false beliefs and a society’s adherence to outdated dogma can eventually tear a community apart.

Hayat scratches at dry skin on her feet, skin that turns to scales when she gets them wet; the physical change that 12 year-old girls experience is central to Hayat’s complexity. The young woman (whose name means ‘life’ in Arabic) fights for her survival with a determination that slowly dawns on her and with the fierceness that the men fear in her underwater sisters. Like Paikea, portrayed by Oscar-nominee Keisha Castle-Hughes in Caro’s adaptation of Witi Ihimaera’s Maori fable, Hayat is a truly modern heroine of understated resilience and, quite literally, the future of her people.

As pure genre cinema, Scales lands some truly mesmerising scenes, not least of which is the terrifying moment a mermaid, dragged from the sea, crawls toward Hayat across a ship’s deck. DOP João Ribeiro proves a master of the black-&-white mood and composition, both on land and at sea; shot on the jagged, majestic coast of Oman, Scales is a gorgeous looking film. The final moments, drenched in the hope that a new and prosperous future lays ahead, are wondrous frames of film.

Representing one of the strongest feature debuts to ever emerge from the region, Shahad Ameen announces herself as that most special of filmmakers - a storyteller that can work timely subtext and scathing commentary into a great work of fantasy.

Fantasy,

Fantasy,  Feminism,

Feminism,  International Film

International Film