VALE JOHN PILGER: FIVE FILMS TO WATCH

Monday, January 1, 2024 at 11:21AM

Monday, January 1, 2024 at 11:21AM

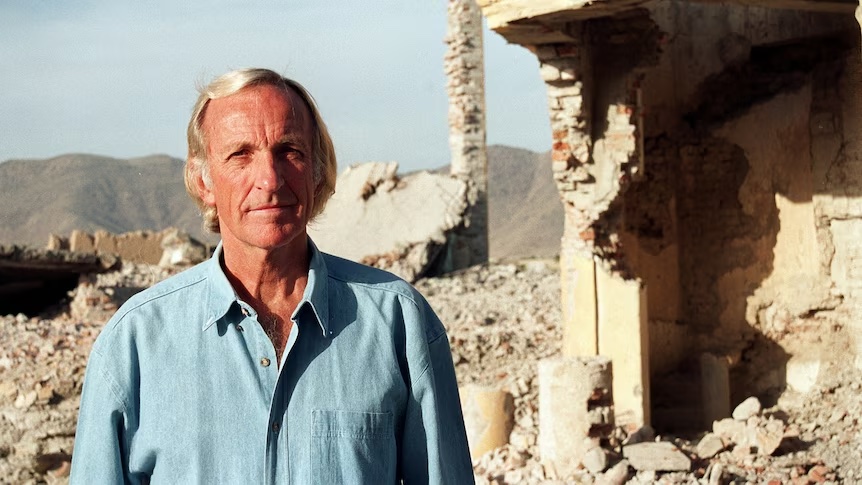

Australian journalist and documentarian John Pilger has passed away, aged 84, in his London home. Born in Sydney’s Eastern suburbs, Pilger would become the most important and influential factual filmmaker in his nation’s history. His camera and his pen captured, with acute insight, the geopolitical turmoil in many of the world's most dangerous zones of conflict, while also profoundly recording the human suffering left in the wake of wars.

From 1963 to 1986, Pilger was a reporter, sub-editor, feature writer and, finally, Chief Foreign Correspondent for U.K.’s Daily Mirror, a role that saw him on the ground as a war correspondent in such hotspots as Vietnam, Cambodia, Egypt, India, Bangladesh, Biafra and the Middle East. The experience would steel his resolve in the face of often shocking inhumanities to expose the brutality of dictatorships and regimes, a focus that led to his most important work as a fearless writer and director of often incendiary documentary works.

Here are five of his works that exemplify the integrity and power of his filmmaking…

VIETNAM: THE QUIET MUTINY (Writer, Presenter / Directed by Charles Denton; 1970) Pilger's first film, broadcast September 28 1970, on the British current affairs series World in Action, broke the story of insurrection by American drafted troops in Vietnam. In his classic history of war and journalism, The First Casualty, Phillip Knightley describes Pilger's revelations as among the most important reporting from Vietnam. The soldiers' revolt – including the killing of unpopular officers – marked the beginning of the end for the United States in Indo-China.

WATCH HERE: Vietnam: The Quiet Mutiny from John Pilger on Vimeo.

YEAR ZERO: THE SILENT DEATH OF CAMBODIA (Writer, Presenter / Directed by David Munro; 1979) Pilger’s landmark documentary alerted the world to the horrors wrought by Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge. His spontaneous, vivid reporting of the power politics that caused such suffering is a model of anger suppressed. Originally broadcast on commercial television in Britain and Australia without advertising, Year Zero won many awards, including the Broadcasting Press Guild’s Best Documentary and the International Critics Prize at the Monte Carlo International Television Festival. Pilger won the 1980 United Nations Media Peace Prize for ‘having done so much to ease the suffering of the Cambodian people’. The British Film Institute lists Year Zero: The Silent Death of Cambodia as one of the ten most important documentaries of the 20th century.

WATCH HERE: Year Zero: The Silent Death Of Cambodia from John Pilger on Vimeo.

DEATH OF A NATION: THE TIMOR CONSPIRACY (Writer, Presenter / Directed by David Munro; 1994) Pilger has said that the making of Death of a Nation: The Timor Conspiracy, about genocide in East Timor following the Indonesian dictatorship’s 1975 bloody invasion and occupation, as”the most challenging to my sense of self-preservation and the most inspirational”. With concealed Hi-8 video cameras, Pilger and director David Munro entered the country clandestinely, and were able to capture footage of mass graves and accounts of widespread slaughter of resistors to Suharto’s reign. Death of a Nation is journalism and history as topical today as it was 30 years ago; members of the UN Human Rights Commission credit the documentary with influencing their decision to send a special envoy on extrajudicial executions to East Timor to investigate massacres such as the infamous Santa Cruz cemetery.

WATCH HERE: Death of a Nation: The Timor Conspiracy from John Pilger on Vimeo.

BREAKING THE SILENCE: TRUTH AND LIES IN THE WAR ON TERROR (Writer, Presenter / Co-directed with Steve Connelly; 2003) Six months after the invasion of Iraq in March 2003 and two years after the invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, Pilger’s documentary highlighted the hypocrisy and double standards of the American and British military misadventures, actions which led to the deaths of more than a million people. “What are the real aims of this war and who are the most threatening terrorists?”, he poses. Interviews with administration officials – described by former CIA analyst Ray McGovern as ‘the crazies’ – are perhaps the highlight of a film made when 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq were raw. The film achieved something of a ‘cult’ status in America, thanks in part to McGovern, who took the film on a screening tour of campuses and small towns.

WATCH HERE: Breaking the Silence: Truth and Lies in the War on Terror from John Pilger on Vimeo.

THE COMING WAR ON CHINA (Writer / Director; 2019) His 60th documentary and arguably his most prescient, The Coming War on China was completed in the month Donald Trump was elected US President; the film investigates the manufacture of a ‘threat’ and the beckoning of a nuclear confrontation. When the United States, the world’s biggest military power, decided that China was a threat to its imperial dominance, two-thirds of US naval forces were transferred to Asia and the Pacific. Seldom referred to in the Western media, 400 American bases now surround China, in an arc that extends from Australia north through the Pacific to Japan, Korea and across Eurasia to Afghanistan and India. The Coming War on China was broadcast on ITV-UK and SBS Australia, as well as China, where a pirated version was shown to possibly its biggest audience.

WATCH HERE: The Coming War on China from John Pilger on Vimeo.

(SOURCE: https://johnpilger.com/, with thanks)

Documentary,

Documentary,  Journalism,

Journalism,  Obituary

Obituary